Citing a need to remain flexible at a time when a growing number of craft breweries are experimenting with non-traditional beer offerings, the Brewers Association (BA) today announced that it has once again revised its “craft brewer” definition.

The changes to the definition, which will take effect immediately and impact the way the trade group reports its 2018 craft beer production figures, marks the fourth time the organization has altered the criteria since 2007.

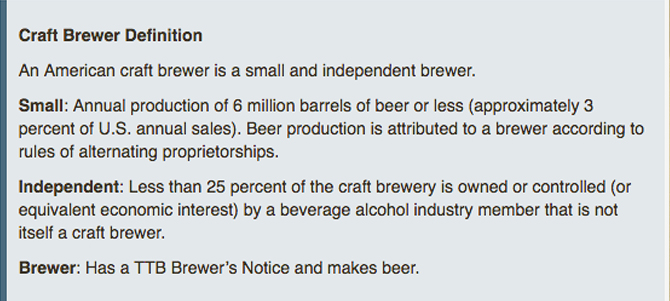

The BA, which represents the interests of small and independent U.S. craft beer companies, said its board of directors approved a revised craft brewer definition that replaces the “traditional” pillar with a simpler “brewer” stipulation.

The elimination of the “traditional” pillar also further underscores the BA’s effort to prioritize the “small” and “independent” components of its definition.

Under the previous definition, a craft brewer was defined as small (producing fewer than 6 million barrels), independent (less than 25 percent owned by a non-craft brewer), and traditional (a majority of its total volume must be derived from traditional or innovative brewing ingredients).

“The Brewers Association craft brewer definition is more relevant than ever in this climate — particularly the ‘independent’ piece of the definition,” the BA wrote in an FAQ that accompanied the announcement. “The shift helps allow for innovation and ingenuity.”

Moving forward, BA-defined craft brewers will no longer need to derive a majority of their volumes from beer. In addition to meeting the small and independent pillars of the organization’s definition, a BA-defined “craft brewer” must possess a Brewer’s Notice from the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) and “make beer.”

Additionally, the new definition enables companies that primarily engage in the act of cider-making, wine-making and hard seltzer production, but also hold TTB Brewer’s Notices and brew small amounts of beer, to be counted in the BA’s annual craft brewer data set.

In an email to Brewbound, BA president and CEO Bob Pease said “a majority” of the group’s members who weighed in on the proposed changes to the definition were in favor of a revision. However, Pease declined to share details of the board’s vote to alter the definition.

According to Pease, the “traditional” pillar of the previous definition “stifles” innovation tactics that BA members are “using to survive or succeed.” Had changes not been made, he said the organization would have been forced to exclude an increasing number of members that have chosen to diversify their beverage portfolios beyond beer from its annual report on craft beer production volumes.

“We needed to keep up with the innovations now and attempt to create a definition that builds in room for future innovations,” he wrote. “The purpose of the definition is not to limit craft brewer creativity, but to allow for it. The last time the definition received an update in 2014, sparkling seltzers weren’t even part of the conversation. Who knows what is next?”

Pease added that future revisions of the definition — which he called “a living document” — are likely, and those adjustments will be necessitated by “innovation, legislative conditions, customer preferences, and/or unforeseen circumstances.”

More immediately, however, the updated definition enables the BA to continue calling Boston Beer Company a “craft brewer,” and thus, count nearly 8 percent of total BA-defined craft beer volumes in its annual industry report.

Boston Beer — which produces the Samuel Adams, Angry Orchard, Twisted Tea, and Truly Spiked & Sparkling product lines — was at risk of falling outside of the BA’s craft brewer definition at the conclusion of this year, as sales of its “traditional” beer offerings have declined and as production of its hard seltzer, cider, and alcoholic tea products have increased.

For his part, Pease said he wasn’t sure if more than 50 percent of Boston Beer’s volumes would have come from non-beer products, because the company is publicly traded and does not disclose the specific production figures for each of its brands.

By stripping away the “traditional” requirement from the definition, the BA will no longer need to estimate production volumes in order to determine whether a company can be included in its craft beer data set, Pease added.

“One benefit of the new definition is we are no longer left with the uncertainty of product percentages yet have to make decisions about how a company fits the definition,” he said.

Nevertheless, the definition change was met with criticism from at least one BA member.

Adam DeBower, co-founder of Texas’ Austin Beerworks, tweeted that the revised definition “doesn’t reflect the [BA’s] membership.”

“I am a brewer, not a spiked seltzer or flavored malt beverage maker,” he wrote. “Ask a shift brewer if he or she got into this industry to make that crap and see what they say.”

The proposed changes were first revealed at the end of October, when Left Hand Brewing founder Eric Wallace, who also serves as the chair of the BA board, penned a note to members presenting the idea of an altered definition that did not include the “traditional” pillar.

As Brewbound reported at the time, the BA board had begun a review of the definition after discovering that an increasing number of craft brewers were experimenting with non-beer offerings such as FMBs, hard seltzers, cider, mead, sake, and alcoholic kombucha. Other companies had reportedly expressed interest in producing beverages infused with CBD and THC.

In his email to Brewbound, Pease cited a survey of BA members that found about 40 percent of companies were making non-traditional offerings.

In a blog post, BA director Paul Gatza added that the traditional plank had become “outdated” as craft brewers turned to “new sources of revenue to keep their breweries at capacity and address market conditions.”

In a separate blog entry, BA chief economist Bart Watson said the changes to the craft brewer definition would cause only “minor adjustments to the craft data set.” That data set will only tally volume coming from “all-malt and adjunct beers,” and will not include FMBs, hard seltzers, sake or kombucha.

Nonetheless, the revised definition will enable the BA to count beer volumes coming from approximately 100 small brewers who would have otherwise been excluded as a result of their wine and mead production, Watson wrote. Last year, 60 small brewers were left out of the data set.

Meanwhile, the BA board also approved the formation of a political action committee (PAC), which will be focused on making permanent the tax credits in the Craft Beverage Modernization and Tax Reform Act (CBMTRA) that were signed into law in December 2017 and will sunset at the end of 2019.

CBMTRA reduced the federal excise tax from $7 to $3.50 per barrel on the first 60,000 barrels for domestic brewers producing fewer than 2 million barrels annually. The legislation also cut the federal excise tax to $16 per barrel on the first 6 million barrels for all other brewers and beer importers while maintaining the $18 per barrel excise tax for brewers producing more than 6 million barrels.

Pease called the formation of a PAC “a recognition that the BA and its members have a maturing and evolving political program.”

“Starting up a PAC is a way of supporting those who have supported America’s small, independent craft brewers,” he wrote. “We’ll still be doing lobby days. We’ll still be welcoming members to our breweries back home. Now, we’ll be supporting those who have demonstrated that they support America’s small brewers.”

Additionally, BA board has amended its bylaws to create a new voting member class for taproom breweries. Those beer companies are defined as breweries that sell more than 25 percent of their beer on site, do not offer “significant food service” and make less than six million barrels of beer annually.