Editor’s Note: Kary Shumway is the founder of Beer Business Finance, an online resource for beer industry professionals. He has worked in the beer industry for over 20 years as a Certified Public Accountant and currently serves as the Chief Financial Officer for Clarke Distributors, Inc. in Keene, New Hampshire.

Beer Business Finance publishes a weekly beer industry finance newsletter, offers guide books on topics such as sales compensation planning, SKU management and financial literacy, and produces a weekly podcast. The newsletter (with a free six month trial), industry guides and podcast are all available at www.BeerBusinessFinance.com.

In part I of his two-part column for Brewbound Voices, published yesterday, Shumway described the inner workings of a beer distributor. In part II, Shumway explores the challenges and opportunities of craft beer SKU proliferation, and offers financial tips for distributors looking to more effectively manage their own complex beer portfolios.

Change is Constant

Beer distributors have been adapting to changes in the marketplace, on one level or another, for decades. When retailers asked distributors for greater levels of service, the merchandising department was created. Stocking the shelves, once a function of the retail store owner, became a service provided by the distributor. This was a new layer of cost for distributors, but an added value to the retailer.

As on-premise accounts added more draft lines, distributors were asked to clean the lines and assist with repairs or new installations. As a result, a draft department was created. This required hiring a new type of employee, one who was specially trained in servicing draft systems.

As the market demanded new point-of-sale materials – sell sheets, menus, banners — the sign making department was created. This allowed the distributor to create real-time, customized materials for retailers.

None of the changes noted above – merchandising, draft line cleaning, or sign-making – seem to fit the traditional definition of a distributor. A distributor buys product from the brewery, and delivers it to the retailer. But there’s a lot that happens in between, and value added that isn’t apparent.

Distributors have lived with change as a constant partner. They have evolved and adapted to the changing needs of the marketplace.

So what makes the SKU proliferation of the past decade, and the level of associated changes, different from the above-mentioned service layers?

The Challenges and Opportunities of Craft Beer SKU Proliferation

That rapid increase in craft SKUs created a ripple effect of changes throughout the distributor organization. Every department, every employee has been impacted in some way. Sales and customer service have been presented with dozens of new brands to learn; warehouse teams have been challenged to make room for hundreds of new SKUs; and the accountants have been tasked with finding a way to pay for it all.Thirty years ago, an average beer distributor carried less than 100 SKUs, but today has well over 1,000.

Despite the myriad of changes, the major impact of SKU proliferation on distributors comes in the form of increased inventory carrying costs.

Inventory Carrying Costs

The purchase of inventory is the single biggest expense and outlay of cash for a beer distributor. Therefore, the monitoring, managing and measuring of inventory levels is critical to profitability and even viability as an ongoing business.

Distributors measure their inventory efficiency using the Days on Hand calculation. In essence, the calculation measures how long a distributor has to hold on to inventory before it is sold. In a perfect scenario, inventory would be received from the brewery and delivered to the customer right away. In reality, the distributor is receiving and paying for inventory well before it is shipped to the retailer.

In general, larger breweries have higher volume packages which turn over more quickly. This allows the distributor to see a faster return on the inventory investment. Inventory is purchased at cost, and sold to the retailer at a profit. The days on hand calculation tells the distributor the wait time between investment (payment for inventory) and return on investment (sale to retailer).

Conversely, smaller craft breweries tend to have lower volume packages, which turn over more slowly. This lengthens the cash cycle for the distributor, and the related days on hand in inventory measurement. The longer the product takes to turnover, the longer the wait before the distributor can convert the inventory back into cash to fund operations. The trade-off for the longer wait comes in the form of higher gross profit. On average, the gross profit for a case of craft beer is higher than that of non-craft.

In the recent past, a typical beer distributor might carry around 20 days of inventory on hand. Product order fulfillment times from larger breweries might be 7 to 10 days between order and receipt, so carrying 20 days of inventory was more than enough to meet market demand. With the increase in the number of slower moving, higher dollar value craft beer SKUs, distributors have seen their inventory days on hand, and related inventory value increase significantly.

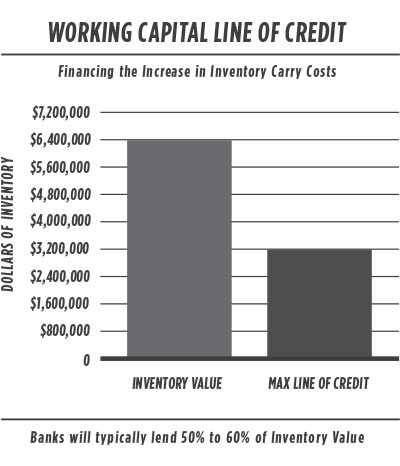

For illustration, take a hypothetical distributor with 25 days on hand and $4 million of inventory. When the days on hand increases to 35 or 40 days, the related carrying cost of the inventory increases as well. What was previously a $4 million investment in on hand inventory becomes $5.6 million at 35 days on hand, and $6.4 million at 40 days on hand. The increase puts a strain on cash flow, and requires that adequate working capital or borrowing capability is in place.

SKU proliferation not only increases the carrying value of inventory – the amount of dollars invested in product — it leads to an increase in out of code or stale-dated inventory. Craft beer products tend to have a shorter shelf-life and a tighter window to be sold through to the customer. Since product may arrive at a distributor warehouse many days or weeks after being brewed, the clock has started ticking on the shelf life. Product that doesn’t sell quickly enough may go bad in the warehouse, or at the retailer location. Either way, distributors typically absorb the cost of the out of code product as well as the costs of disposal.

How distributors responding and continuing to adapt to SKU Proliferation

- Improved inventory portfolio management

- Better process and oversight of stale-dated products

- Increased working capital line of credit and borrowing capability

Improved Inventory Portfolio Management

With the rapid increase of brands and packages, an active and aggressive portfolio management process is imperative. This process includes a comprehensive brand rollout plan for new packages, and a regular review and focus on existing brands. SKUs should be reviewed regularly to determine if they deserve to be in the portfolio. Simply put, if products don’t sell, they shouldn’t be in the portfolio.

The portfolio management process should identify under-performing products and put them on a track to be corrected. As Jack Welch, the former chairman and CEO of General Electric said regarding under-performing business units, “fix it, sell it, or close it.” The same applies to portfolio management.

Inventory portfolio management involves being a curator – this means being selective when choosing the products that get presented to retailers. The distributor’s job is to get the right products, into the right accounts, at the right time and at the right price. It does not, and should not include trying to sell every product to every account.

The portfolio management process is a mixture of art and science. Distributors understand the market and have a good feel for what products will be a good fit. This is the intuition, experience, the business acumen, and the art of portfolio management. The science of portfolio management involves some math – sales volume, trends, velocity, points of distribution and chain authorizations among other factors.

There’s no one-size fits all approach to portfolio management. The only requirement is that the process actually happens. Some distributors may use 80/20 analysis — the Pareto principle — to identify and reduce under-performing SKUs. Others may use another Jack Welch approach: “fire the bottom 10%.”

However, most distributors take a thoughtful and considered approach to portfolio management. It’s in everyone’s best interest – consumer, retailer, brewery and distributor — to help the brand or package succeed. For distributors seeking new ideas to improve their portfolio management process, the SKU guide may be of service.

Better process and oversight of product code dates

Distributors should closely monitor product code dates to ensure that the beer is delivered to market well before the expiration of its shelf life. Many beer packages contain a “Born on” or “Best by” date to indicate when the product needs to be consumed. Once the package goes out of code it should not be sold and should be destroyed.

When the distributor purchases product from the brewery, they own it. If the product doesn’t sell by the end of the shelf life, the product must be destroyed and distributors bear the full brunt of the cost. In addition to eating the cost of the product, there is a cost involved with disposal and destruction of the product, typically 50 cents to over a dollar per case.

With the increase in SKUs and overall inventory value, the incidence of out-of-code product write offs increases as well. Major beer labels typically have code dates in excess of 100 days, while craft beers tend to have shorter lifespans. The decrease in shelf life, combined with the increase in number of products to manage, leads to more out of code beer, and higher expenses for distributors.

To lessen the amount of old beer that gets dumped, distributors have had to improve the process of managing close coded products. This has always been a major focus item for distributors – no one likes to throw out beer – but these days it’s more important than ever.

In response, distributors are more diligent with clearly marking code dates on product in the warehouse, insisting on proper product rotation, and providing incentives or penalties to sales people for too much out of code as a percentage of sales. Measuring, managing and communicating out of code product as a percentage of sales has become vitally important.

The circle of responsibility for managing old beer has widened as well, with virtually everyone in the organization checking product codes – merchandisers when they stock shelves, drivers when they rotate the cooler, sales people when they build displays and the warehouse team when managing product on the floor. It takes a village to manage out of code product, and the best distributor villagers are active and engaged.

Increased working capital line of credit and borrowing capability

As distributors invest more cash in inventory growth, they are left with fewer dollars to fund operations, make capital expenditures and re-invest in the business. Payroll must be made, the utility bill has to be paid and running out of cash isn’t an option.

As a consequence, distributors must turn to their bank to set up a working capital line of credit to fund cash shortfalls. What was once paid for with cash is now paid for with borrowed money. This leads to increased interest expense on the income statement and additional leverage on the balance sheet in the form of debt.

In the past, using working capital lines of credit to fund seasonal increases in inventory was not unusual. Money would be borrowed in the spring to fund the inventory build in preparation for the summer selling season. The line of credit borrowing would be re-paid in the late summer using cash from operations. However, with the growth in the number of SKUs and increase in inventory, the utilization of working capital lines of credit and related interest expense are now a year-round reality.

In Summary

With the tremendous growth in craft brands and SKUs, the increase in inventory carrying costs is one of the biggest challenges facing distributors. In response, distributors are working on improved inventory portfolio management, better process and oversight of stale dated products, and adding working capital lines of credit to enhance borrowing capability.

The craft beer revolution presents many opportunities for the beer distributor – higher margin packages, more products to fill excess capacity on delivery trucks, and a growing segment to help offset declining sales of major beer brands. However, to take advantage of these opportunities, today’s beer distributor must continue to evolve and improve to stay competitive.

Change has been a constant partner, and SKU proliferation is just one more big change requiring adaptation in the business model of the beer distributor.

About Brewbound Voices:

Brewbound Voices was created with the goal of providing readers valuable insight into areas like finance, investment, branding, marketing, sales, and distribution. The column serves as an avenue for experts to contribute their knowledge to our readership. Interesting in writing for Brewbound Voices? Email pitches to news@brewbound.com.