The conclusion drawn from Demeter’s new report, “Protecting Craft Against Pseudos,” is that “consumers do not differentiate craft and craft-positioned pseudos.”

What is a “pseudo” craft brand exactly? According to Demeter, brands like the MillerCoors-produced Blue Moon and Anheuser-Busch InBev’s Shock Top fit the bill because neither falls under the Brewers Association’s definition of craft, despite being marketed as higher end products.

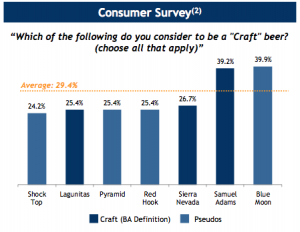

Of the 650 men the firm surveyed through Google Consumer Surveys, 39.9 percent considered Blue Moon (a so-called pseudo) to be craft. Comparatively, 39.2 percent identified Samuel Adams, which does fit the BA’s definition of craft, as such.

Demonstrating the confusion that consumer face, five other brands, some that are BA-recognized and some that are “pseudos” — Lagunitas, Sierra Nevada, Redhook, Pyramid and Shock Top — were also perceived as “craft” by consumers, albeit less frequently.

Lagunitas and Sierra Nevada (BA approved) were considered craft by just 25.4 and 26.7 percent, respectively, of those surveyed. Similarly, Redhook — part of Craft Brew Alliance, which is partially owned by A-B InBev and also deemed a “pseudo”by Demeter — was considered craft by 25.4 percent of survey participants; Pyramid, which is owned by North American Breweries, tallied the same figure. Shock Top, with the lowest number, still garnered craft approval of 24.2 percent.

Marc Levit, an associate with Demeter, said the co-mingling of craft brands and so-called “pseudo” brands in the retail tier makes it difficult for consumers to differentiate between the two.

He said retailers could stand to benefit from more help in distinguishing the two, but to levy the entire responsibility on them would be unfair.

“I don’t think it’s the supermarket’s responsibility, that’s putting a lot of the onus on them.”

Despite the apparent overlap in perception of craft and “pseudo” craft, Levit said he does see the consumer still becoming increasingly aware of who manufactures the beer they drink.

“I’m starting to see Shock Top ads everywhere I go,” he added. “I think consumers are starting to see some of this advertising on a macro level. I think they’re starting to question how a brand that we thought was kind of small and local and craft can have such a large advertising budget.”

Despite this apparent differences, the report also counts on the continued growth of BA-recognized craft in the marketplace. It projects the category’s retail dollar share to grow to 25.3 percent by 2020 (up from 14.9 percent now), assuming a yearly increase of approximately 2 percent.

Still, by positioning products as artisan, small-batch, or historic, the report adds that distinguishing craft from “pseudo” will remain a murky task.

But asked whether a clearer distinction between craft and the so-called pseudo brands is necessary, Levit said that would be best left up to the people who put their “heart and passion” into brewing.

“Is it right to tell someone that their beer fits or doesn’t fit in a definition?” he questioned.